For the experts.

All the following equations and parameters are described in the Theory

page.

Intuitively, decreasing the uplift rate may be equivalent to increasing the

rainfall rate in terms of mountain height. We can evaluate the equivalence of

changing parameters by rewriting the equation in a ”non-dimensional” form. For

example, instead of having elevation z we will have z dividing by some constant

reference elevation, or a scaling factor, let’s say H, and this will give us

z*, an elevation but without dimension. Its unit is ... an arbitrary unit of

elevation. We do that for all the parameters, replace them into the original

mass-balance equation and look at the resulting new equation, that will have some

universal meaning as all its parameters have an arbitrary unit of length, time

etc.

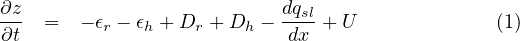

So we start with the initial mass balance equation (cf Theory page.)

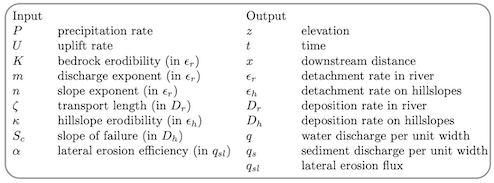

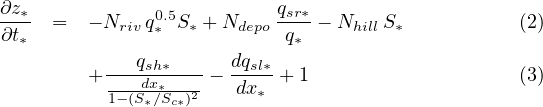

Then, with m = 0.5 and n = 1 and using the scaling factors H for mountain height, L for mountain width, P for effective precipitation rate (runoff) and U uplift rate, H∕U for time, we obtain the non-dimensional form (*) of the mass balance equation 1 (Carretier et al., 2018):

where

Nriv = KU-1P0.5L-0.5H

Ndepo = ξ-1P-1

Nhill = κHU-1L-1

These numbers are called ”non-dimensional numbers” (Rmq. Ndepo is G in Guerit

et al. (2019) - see the post about the scaling between mountain height and rainfall).

These numbers say that for two simulations 1 and 2 with different parameters but

such that their non-dimensional numbers are the same, then the evolution of the

mean non-dimensional erosion (ϵ1∕U1 and ϵ2∕U2) over non-dimensional time

(t1 * U1∕H1 and t2 * U2∕H2) or the final non-dimensional mountain height (z1∕H1

and z2∕H2) will be similar. Experts can read Whipple and Tucker (1999).

In particular, let’s imagine two simulations with K1 = 2K2 and U1 = U2∕2. Then

non-dimensional numbers are the same in both cases and it can be predicted that the

evolution of the landscape will be similar in both cases. In other words, doubling the

erodibility or reducing the uplift rate by 2 have the same effect on the topography.

It is moreover a problem to interpret the different altitudes of mountains

in terms of tectonic uplift because their erodability is generally unknown.

However, this analysis does not predict everything. For example, the relative

effect of U and P is difficult to establish because the parameter chosen for the

altitude H, which is the final altitude of the mountain, itself depends on P and

U. Similarly, as explained in the post ”The scaling of mountain relief with

rainfall”, the relative weight of U and P depends on ζ, the transport length

parameter.

Suggestion for teaching:

From dimensionless numbers, predict the equivalence between some parameters and

verify this equivalence using the site simulations.

Re-write the non-dimensional equation with other scaling factors and discuss the

resulting non-dimensional numbers.

References

Carretier, S., Y. Godderis, J. Martinez, M. Reich, and P. Martinod (2018), Colluvial deposits as a possible weathering reservoir in uplifting mountains, Earth Surface Dynamics, 6(1), 217–237, doi:10.5194/esurf-6-217-2018.

Guerit, L., X.-P. Yuan, S. Carretier, S. Bonnet, S. Rohais, J. Braun, and D. Rouby (2019), Fluvial landscape evolution controlled by the sediment deposition coefficient: Estimation from experimental and natural landscapes, Geology, 47(9), 853–856, doi:10.1130/G46356.1.

Whipple, K. X., and G. E. Tucker (1999), Dynamics of the stream-power incision model: implication for heigth limits of mountain ranges, landscape response timescales, and research needs, J. Geophys. Res., 104, 17,661–17,674.